Monika Stempkowski[*]

Contents

II. Custodial Measures pursuant to § 21 para. 2 ACC p. 43

B. Developments, Crimes, and Psychopathology p. 47

C. Recidivism after Release p. 51

IV. Empirical Study of the Declining Recidivism Rate p. 55

A. Hypotheses, Sample, and Methodology p. 55

B. Results and Discussion p. 57

Since 1975, the Austrian Criminal Code[1] has contained specific regulations for dealing with mentally ill offenders. Instead of serving time in jail, these offenders are detained in specialized facilities until they no longer pose a threat to society. In recent years, these custodial measures have been frequently criticized. Not only has the number of people detained within this kind of confinement increased drastically, they also spent significantly longer periods of time in the facilities before being released on parole.[2] Furthermore, the quality of the expert reports, which are delivered mostly by psychiatrists in order to support the decisions of the court whether to detain or release an offender, has been criticized heavily.[3] Contrary to these unpleasant developments, the number of people who relapsed into crime after having been released from a custodial measure declined almost steadily.[4]

The following study examines this phenomenon with regard to offenders who were detained pursuant to § 21 para. 2 ACC, thus suffering from a mental illness but still committing the crime in a state of accountability. The following article provides an overview of the current situation of the detained persons in a custodial measure before selected results of the empirical study will be reported and recommendations derived from the data will be discussed.

The Austrian criminal law is based on the principle of culpability, as regulated in § 4 ACC: “no punishment without guilt”. However, the applicability of this principle is limited in situations where an offender has only limited control over his or her behavior due to reasons such as mental incapacity or intoxication. In order to take into account that special regulations are needed to react to people with psychological disorders committing crimes, the system of ‘Preventative Measures’ was installed in the Austrian Criminal Code (§§ 21 – 23 ACC). The basis for detaining people in a custodial facility is not guilt, but the danger stemming from their mental illness and consequentially the responsibility of the state to protect society.[5]

If a person commits a crime that would be punishable with a term of imprisonment exceeding one year, and in doing so the person is affected by a mental incapacity resulting from a serious psychological illness, the offender cannot be sentenced to serving jail time, but instead has to be placed in a mental health facility. This rule only applies if due to the person’s character, condition and the nature of the crime there is reason to fear that the perpetrator will commit another offence involving serious consequences (§ 21 para. 1 ACC). Furthermore, if a person is affected by a mental illness, but can still be held accountable for his or her actions due to a lack of mental incapacity, he or she shall also be sent to a mental health facility and additionally, a prison sentence shall be passed (§ 21 para. 2 ACC). Custodial sanctions cannot be based on offences against property, unless the commission of the offence involves the use of force or an immediate threat against life or physical integrity.

Mental incapacity is defined in § 11 ACC: if the person, at the time of committing the offence, is in such a state of mental disease, mental disability, serious disturbance of consciousness or in a similarly serious disturbance of the mind as to deprive the person of the capacity to understand that the person’s conduct is wrong or, if the person does know the conduct is wrong, deprives the person of the capacity to act accordingly. In this case, § 21 para. 1 ACC is applied.[6] However, if the person did not lack these abilities but nevertheless committed the crime affected by mental or psychological abnormity, § 21 para. 2 ACC is applied, and he or she is also committed to a custodial facility. The term “mental or psychological abnormity” as used in § 21 ACC describes a legal concept which does not necessarily correspond to mental illness as it is understood in psychiatry or clinical psychology.[7]

Unlike regular prison sentences, the detention in a mental health facility is imposed without a fixed duration. The offender has to remain within this facility as long as he or she poses a risk to society attributed to the mental illness.[8] Every year a court decides whether the detention is still necessary or whether the detainee can be conditionally released on probation. This yearly review has to be conducted ex officio; additionally, the detainee has the right to apply for a review.[9] However, if the offender upon committal received a prison sentence as well and the time in detention was shorter than the prison sentence, the person has to serve the remaining time in prison, unless he or she is also released conditionally from this prison sentence.[10] When released conditionally from confinement, a period of parole has to be set. This probation period is usually ten years; however, if the offence for which detention was imposed is punishable by imprisonment of no more than ten years, the parole period is only five years.[11]

Offenders committed under § 21 para. 2 ACC should be held in specialized penitentiaries, better equipped to support the detainees in their process of resocialization than regular prisons. Currently, there is one such specific institution, located in Vienna’s fifth district and called ‘Justizanstalt Mittersteig’.[12] Since this facility can only accommodate 150 detainees, other institutions have to be used as well. § 158 para. 5 Corrections Act[13] allows for offenders detained under § 21 para. 2 ACC to be confined in specialized departments of regular prisons. Currently, there are specialized departments in the prisons in Krems, Garsten, and Graz-Karlau.[14]

As mentioned above, there has been intensive criticism of the system of custodial sanction for many years. In 2010, the Austrian Court of Audit published a report listing various deficiencies of the system, as for example that the Ministry lacks an overall strategy concerning the custodial measures and that there is no clarity concerning the costs of the confinement both within the penitentiary system as with external partners such as aftercare facilities.[15] Additionally, the terms currently used in the Austrian Criminal Code are seen as reason for complaint, since the term “mental or psychological abnormity” as used in § 21 ACC is outdated and discriminating.[16]

In 2014, a Viennese newspaper published an article[17] about a detainee in a poor state of health in one of the penitentiaries, causing the Minister of Justice to install an expert working group assigned with the task of compiling a report, which should include proposals on how to improve custodial measures. This report was published in 2015, containing comprehensive suggestions for improvement.[18] For example, specialized legislation was proposed, regulating exclusively the custodial sanctions. Further, commitment into custody should only be possible in case of a crime punishable with a term of imprisonment exceeding three years. Additionally, the expert group suggested the opening of ‘therapeutic centers’ detached from the regular prison system and solely focused on treatment.

In 2017, the then called Federal Ministry of Justice published a draft legislation proposing a comprehensive reform of the custodial sanctions by introducing a specialized legislative act called ‘Maßnahmenvollzugsgesetz’.[19] Further, amendments to the Austrian Criminal Act, the Code of Criminal Procedure[20] and the Corrections Act were proposed. The proposed legislation contained many of the suggestions made by the expert group in 2015, although not all propositions were implemented. However, due to political reasons the Ministry presented the draft legislation in a press conference and also published the documents online, but never initiated a legislative process. Since 2017, no more developments concerning a reform of the current legislation took place.

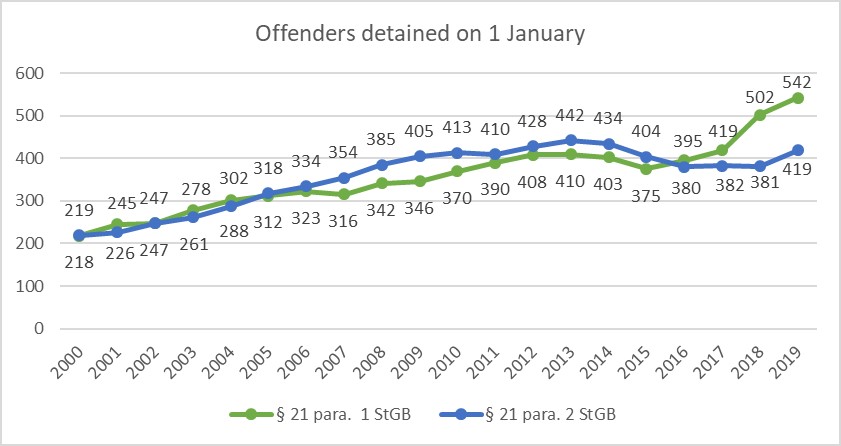

From the 1980s onwards, the number of people given custodial sentences has increased significantly. On 1 January 2000, a total of 437 people were confined under this regulation. This figure rose to 961 people on 1 January 2019. 419 of those people were confined as mentally ill but accountable offenders (§ 21 para. 2 ACC).[21] With regard to the total number of people detained within the Austrian prison system, about 10 % were confined because of a crime committed under the influence of a mental illness.[22]

Graph 1: Number of offenders detained on 1 January every year, 2000 – 2019

Below, the group of mentally ill but accountable offenders will be described in detail; however, similar trends can often be found when looking at the group of offenders acting in a state of mental incapacity.

One reason for the rising number of confined offenders is the increase in committals into custody. In 2000, 34 people were committed to a custodial facility under § 21 para. 2 ACC, in 2018 this number was twice as high with 70 committals all over Austria.[23] Looking at the number of people released every year it becomes evident that this figure has risen as well; however, in most years it was still lower than that of people newly committed, leading to a constant increase of detainees.[24]

Graph 2: Development of committals in and departures from a custodial sanction regulated by § 21 para. 2 ACC, 2000 – 2017

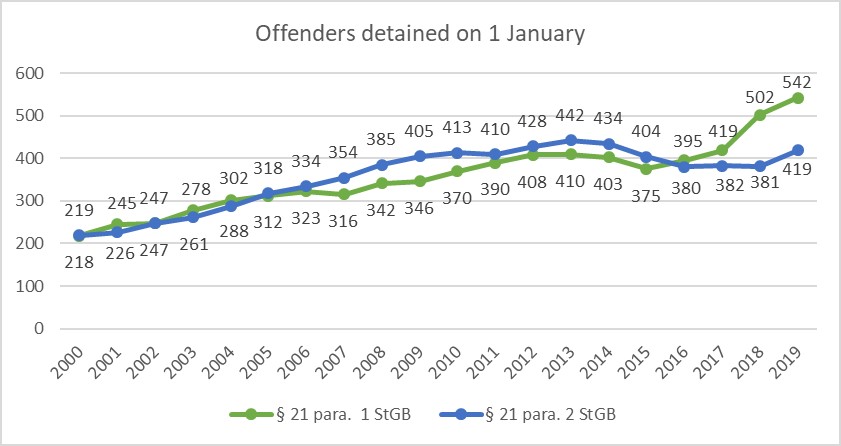

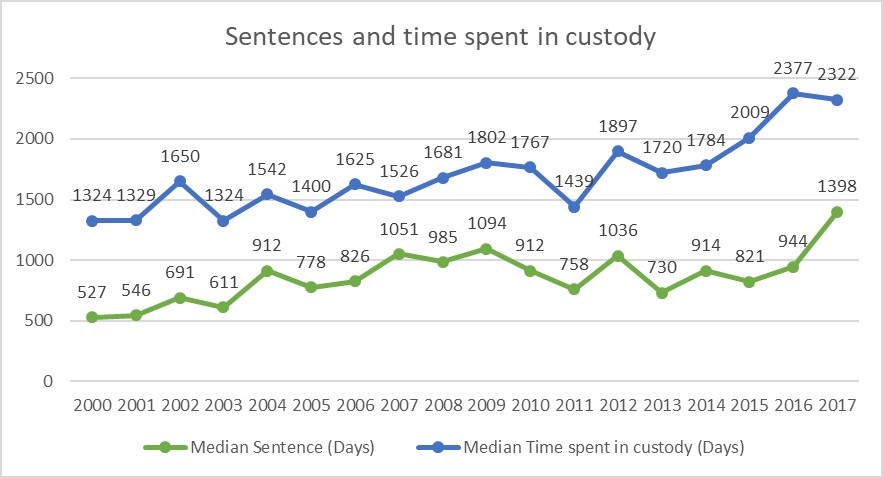

Additionally, the time offenders spent in confinement lengthened over the years.[25] On average, people released in 2000 had spent 3.6 years in detention. For people released in 2018 this figure rose to 5.3 years, increasing by almost 50 %.[26] Since, as explained above, a committal under § 21 para. 2 ACC also involves the imposition of a prison sentence, these numbers can be compared as well. From 2000 to 2017, 82.7 % of the detainees spent more time in confinement than they would have been obliged to considering their prison sentence. In 2018, this was true for 92 %. Concerning the length of the prison sentences, no equivalent development can be identified: in 2000 the judgements convicted the offenders to 2.75 years on average, in 2018 this figure decreased slightly to 2.7 years.[27]

Graph 3: Development of sentences and time spent in custody after a committal applying § 21 para. 2 ACC, 2000 – 2017

In 2012, a study was conducted investigating the psychopathology of the confined offenders as described in the expert reports leading to the committal.[28] A majority of 65 % of the perpetrators suffered from a personality disorder. Within the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), these conditions are listed in the section of ‘Disorders of Adult Personality and Behaviour’. They are characterized by “deeply ingrained and enduring behaviour patterns, manifesting as inflexible responses to a broad range of personal and social situations. They represent extreme or significant deviations from the way in which the average individual in a given culture perceives, thinks, feels and, particularly, relates to others. Such behaviour patterns tend to be stable and to encompass multiple domains of behaviour and psychological functioning.”[29] Frequently, the affected person perceives the disorder as belonging to him- or herself, forming an inherent part of their personality. Ensuing, the people most affected by the disorder are in many cases relatives, friends and other people in the close social circle of the patient. Within a forensic context, the most common type is the dissocial personality disorder. Additionally to the criteria mentioned above, people with this kind of disorder are significantly less concerned with the feelings of others as are healthy people. They are incapable of maintaining stable relationships and they do not adjust their behaviour following punishment. In addition, they frequently show high levels of aggressive and violent behaviour as well as a low tolerance of frustration.[30]

The second largest group of detainees consisted of 20 % diagnosed with a form of mental retardation. About 10 % suffered from schizophrenia, schizotypal, and other delusional disorders. Additionally, a comorbid mental or behavioural disorder due to psychoactive substance use was found.

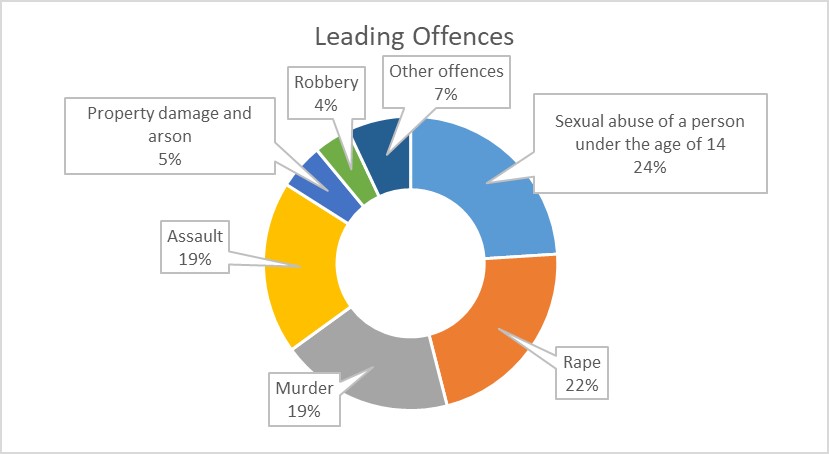

Additionally to examining the mental illnesses common among these offenders, the study explored the types of crimes committed by them, focussing on the most serious offence.[31] In 24 % of the cases, the offenders had committed sexual abuse of a person under the age of 14 (§§ 206 – 208 ACC), 22 % were guilty of offences such as rape, sexual coercion and sexual abuse of a vulnerable or mentally impaired person (§§ 201 – 205 ACC). Thus, almost 50 % of the perpetrators were committed because of an offence against sexual integrity and self-determination. Offences against life and physical integrity, such as murder or manslaughter (§§ 75, 76 ACC) or assault (§§ 125, 126 ACC) had been committed in 19 % of the cases. Offences such as property damage (§§ 125, 126 ACC) or arson (§ 169 ACC) each occurred in 5 % of the cases, 4 % were guilty of robbery (§§ 142, 143 ACC).

Graph 4: Leading offence of persons committed into a custodial sanction in 2010

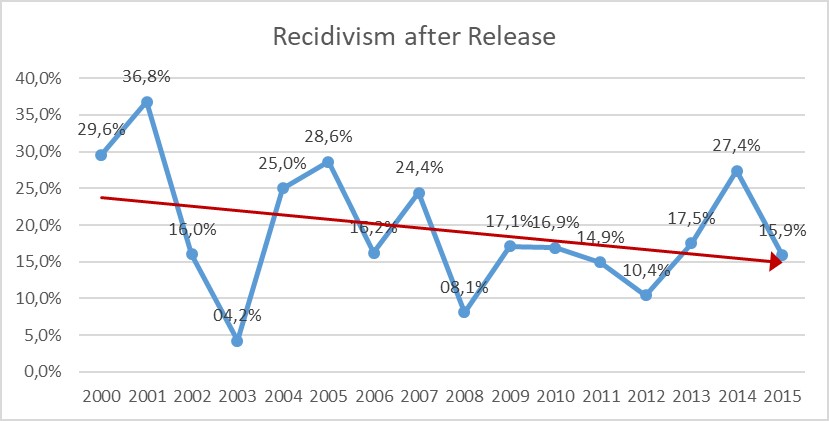

Every year, the Federal Ministry of Constitutional Affairs, Reform, Deregulation and Justice compiles a report monitoring the developments concerning the system of custodial sanctions. Within this report, the recidivism rate of offenders released from a custodial measure is also analysed. The report compiled for the year 2014 was the starting point for the present study.[32] For several years, it had been possible to observe a decline in the recidivism rate, defined as offenders being recommitted into custody or sentenced to imprisonment after a conditional release.[33] This is observed for a period of three and five years starting from release. Concerning the three-year period, the percentage dropped from 29.6 % for offenders released in the year 2000 to 14.9 % for detainees released in 2011.

Graph 5: Development of the recidivism rate after a release from a custodial sanction regulated by § 21 para. 2 ACC, time at risk three years, 2000 – 2015

Compared to the recidivism rate of former prisoners as well as offenders sentenced to a fine, that of former detainees of custodial sanctions is now noticeably lower. Starting to observe the development from the reference year 2010 onwards, the percentage of recidivism concerning sentences apart from committals into custodial sanctions always ranged between 34.1 % and 32.5 % for an observation period of four years. In addition to the difference in the level of recidivism, no comparable changes to the rate of former detainees can be observed.[34]

As mentioned above, not all former detainees return into a custodial sanction. Of all offenders returning into the penitentiary between 2000 and 2018, who were released from a custodial sanction under § 21 para. 2 ACC, only 32 % were recommitted into this kind of custody. 43.5 % received a prison sentence. In 14.5 % of the cases, the former detainees had broken one of the court directives imposed onto them upon release and therefore the conditional release was revoked.[35]

Assessing the risk stemming from the offender due to the mental illness is vital for the whole system of custodial sanctions. In the trial carried out after the initial offence the risk of further delinquency has to be evaluated just as much as every year in the course of the decision whether the offender has to remain in custody or is to be released. In most cases the assessment is done by experts, mainly psychiatrists and psychologists, who provide the basis for the judge’s decision by examining the offender and delivering a report. While the Austrian Code of Criminal Procedure stipulates an examination by a psychiatric expert for the trial leading to the committal, such a procedure is not mandatory for the yearly review of the necessity of further detention (§ 429 para. 2 subpara. 2 and § 438 CCP). Currently, it is not compulsory for a psychological expert to contribute to the process; this is at the discretion of the court.

While the experts thus play a vital role in the process, their work has been criticised considerably in recent years.[36] Several studies examining the quality of the reports produced by the experts in Germany[37] as well as Austria[38] detected serious shortcomings concerning the methods applied as well as the conclusions drawn from them.

However, not only the quality of the experts’ work has been criticized; related circumstances have been regarded as problematic as well. One prominent point of criticism concerns the remuneration experts receive for their work. § 43 para. 1 subpara. 1 lit e Fees Claims Act[39] stipulates that experts receive a lump sum of € 195.40 for their work. If done properly, the production of a risk assessment takes a thorough review of the police file as well as possibly existing medical histories, several extensive conversations with the offender and in some cases talks with relatives or care givers. It is evident that the sum stipulated by law is not adequate for the amount of work, let alone the responsibility borne by the expert for the future of the offender as well as for the safety of society.[40] In 2007, the then Federal Ministry of Justice issued a decree stipulating that experts have to be paid by the hour for the time they need to produce their report.[41] Subsequently, the Higher Regional Court of Vienna ruled in several cases that the lump sum cited above does not constitute adequate remuneration for the work of the expert.[42] However, the criticism did not cease afterwards, which is why the assumption seems justified that not all Austrian Higher Regional Courts follow the ruling issued in Vienna. For example, the low remuneration was criticized in the report of the expert working group installed in 2014, listing several proposals for reform.[43]

In addition to the problem of adequate payment, the missing mandatory education for forensic experts has been criticized[44] as well as the fact that there is no system of quality control in place.[45]

When looking at the international literature, several compilations of minimal standards for risk assessment can be found. For example, a group of experts from different disciplines in Germany developed a list of criteria aiming on the one hand at providing a basis for the work of experts and on the other hand at enabling the judges to critically evaluate the report, even if they lack the specific knowledge necessary for judging its content.[46] Formal criteria, as for example exact information concerning the sources used for compiling the report (e.g. medical and police files, information obtained in the conversation with the offender, relatives and care givers, physical examination, etc.) and listing of the state of the art scientific literature, are demanded, furthermore necessities concerning the content of the report. This includes comprehensive information about the examined individual, his or her background and development, their psychiatric disorder and the delinquency. Risk factors have to be discussed and at the heart of the report, there is an individual hypothesis concerning the genesis of the offender’s delinquency. Further, concrete measures are to be proposed in order to improve the offender’s condition and prevent further criminal offences. For the present study, these criteria formed the basis for measuring the quality of the expert reports examined.

As discussed above, the recidivism rate of offenders released from custodial facilities regulated by § 21 para. 2 ACC has decreased significantly from the year 2000 onwards.[47] The following study, conducted between 2015 and 2018, aims at exploring the circumstances and reasons behind the declining recidivism rate leading to fewer recidivism in later years.

The following three hypotheses were tested:[48]

1. Due to the rising number of offenders committed to custodial facilities, the number of people bearing a lower risk for recidivism from the beginning on has increased over the years. In this case, the declining recidivism rate can be traced back to a change of the population committed into custody.

2. The quality of care and treatment received by the offenders during their time in custody as well as in the caring facilities responsible after release has increased over the years.

3. With time, the selection process has improved, separating offenders ready for release more accurately from those still dangerous and who therefore needed to remain in custody. Consequently, the percentage of people who upon release had a lower risk of reoffending increased.

Additionally, a combination of those developments could also be responsible for the decline.

In order to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the developments and processes potentially leading to the decline in recidivism, quantitative and qualitative measures were applied and subsequently combined by means of triangulation. In a first step, two groups were defined, whose recidivism rate differed considerably. Those groups were then compared with regard to numerous variables in order to ascertain other differences between them, which could provide clues for the question under consideration. Based on an extensive review of the existing literature, variables were chosen which are known to indicate the risk of recidivism, as for example prior convictions, young age, and antisocial personality traits.[49] One group consisted of all male offenders released from a custodial facility regulated by § 21 par. 2 ACC in 2000 and 2001, the other of the men released in 2010 and 2011.[50] By applying this research design, a sample size of 120 persons emerged. By studying court files as well as files created and managed within the custodial facility, information about the offenders was obtained. Certain documents were of specific importance: the police files as well as the judgement, the yearly reports concerning the conduct of the offender in the custodial facility and the court order releasing the offender. Besides, the experts’ reports created mostly by psychiatrists upon committal as well as upon release, if available, were analysed in detail. Apart from providing relevant data for the study, their quality was examined applying the aforementioned criteria. For every criterion, it was assessed whether the report fulfilled it completely, partially or not at all, thereby applying a three-step scale.

In addition to comparing the groups defined by the date of release, another comparison was made: reoffending persons were compared with persons who did not reoffend within a five year period after their release, independent from the year they left the custodial facility.

Subsequently, expert interviews were conducted with professionals dealing with people in this form of custodial facility from different perspectives. Interviews were conducted with judges, representatives of correctional facilities, probationary services, a psychiatric expert as well as representatives of an aftercare facility.

In a first step, basic variables about the detainees were surveyed, as for example at what age they offended for the first time, the number of previous convictions, their marital status, and their level of education. Comparing the two groups distinguished by their year of release, it became apparent that hardly any differences concerning the personal background could be detected. For example, the frequency of different types of crime committed by the offenders did not differ between the groups. Crimes against sexual integrity and self-determination were the most common ones in both groups, followed by crimes against life and physical integrity as well as crimes against freedom and property. On average, detainees had five previous convictions upon committal and almost 50 % had already experienced some form of imprisonment. When they became delinquent for the first time, detainees were 21 years on average.

The sole significant difference between the two groups concerned the nationality of the offenders: while in the first group, released in the years 2000 and 2001, all detainees were Austrian, 18 % of the detainees released in 2010 and 2011 had a different nationality (p = .005). Due to this result, it was tested whether this development might have contributed to the decline in recidivism, since it is possible the foreign nationals left Austria upon release and thereby did no longer pose a risk for reoffending. However, analysis revealed that by extracting the foreign nationals from the group, the recidivism rate increased only from 25 % to 26 %. Therefore, the increase of foreign nationals did not explain the decline of recidivism of the whole group.

Concerning the background of the detainees, special attention was given to the psychiatric diagnoses as described in the expert reports issued during the trial. On the one hand these diagnoses are the basis for the committal of the offender into the custodial sanction, on the other hand they also form the basis for the treatment applied within the care facility. Concerning most disorders, no differences between the groups emerged. In both groups, the majority of offenders was diagnosed with a personality disorder (around 70 %), about 20 % suffered from a sexual preference disorder (e.g. paedophilia). Less common were diagnoses such as mental retardation, schizophrenic disorders and affective disorders. However, concerning mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use a significant difference between the groups emerged. 20 % of the detainees released in 2000 and 2001 were diagnosed with this type of disorder; in the group released in 2010 and 2011, this figure rose to almost 50 % (p = .002). Concurrently, the files and expert reports were surveyed for indications whether the offenders had abused alcohol or illicit drugs during their lifetime. Interestingly, concerning this information no difference between the groups emerged. Consequently, the difference found concerning the diagnoses cannot be traced back to a genuine increase in offenders with alcohol or drug problems. It can be assumed that the observable increase of this diagnosis does not stem from a factual increase but from changes and improvements in the work of the psychiatric experts. Due to an increase in the quality of the reports, diagnoses are given more precisely and comprehensively than in the earlier group. Surveying whether an expert report contained a diagnosis at all yielded this finding: whereas 15 % of reports concerning the detainees released in 2000 and 2001 did not contain a serious diagnosis at all, this figure dropped to less than 4 % for the group released in 2010 and 2011. This difference proved to be significant (p = .042). Additionally, the expert reports were examined as to whether they contained more than one diagnosis. Again, a significant increase was detected (p = .006), from 42 % of reports listing more than one diagnosis in the first group to 72 % in the second group. By listing more than one diagnosis, the expert took comorbidities into account. These results show that in earlier years, experts frequently focussed on one main diagnosis. By focussing on the personality disorder, which, as explained above, dominates the impression of the offender in most cases, the experts were leaving aside possible comorbidities. Disorders due to psychoactive substance use could have been seen as mere comorbidities. In later years, the precision in the work of the experts improved, leading to a stronger focus on comorbidities such as addiction. As a consequence, these additional diagnoses might have found stronger consideration in the treatment of the offender.

Different results were obtained when offenders who relapsed into crime after their release were compared with former detainees who did not reoffend within a five-year period, independently from the year of their release. The results showed that reoffenders differed from non-reoffenders in many variables concerning their background, which were independent from the crime leading to the committal, the treatment, or the circumstances of their release. Reoffenders were significantly younger when first becoming delinquent (p = .000): they were 19 years on average when they were first sentenced, compared to the age of 29 years for the non-reoffending detainees at the time of their first conviction. Also, reoffenders had been convicted on average twice as often as the non-reoffenders before their committal (p = .005) and a significantly larger part had already experienced a form of imprisonment before (p = .028). Differences also became apparent when examining the offences committed that led to the confinement: reoffenders had committed fraud and theft significantly more often than non-reoffenders (p = .007 respectively p = .002). Crimes against property generally show a higher reconviction rate than other offence categories; this result was replicated within the present study. Additionally, multivariate analyses revealed differences between reoffenders and non-reoffenders, always pointing in the direction of reoffenders having committed offences from more categories than detainees who did not reoffend. No significant differences were found concerning the psychiatric diagnoses of the two groups. Taking into account that all of the differences detected between those groups already existed at the time of the crime and the committal, a picture of a highly burdened group of detainees became apparent, possibly giving the professionals and caregivers within the correctional facility a first impression concerning the risk of reoffending.

In contrast, as described above, those differences were not found when comparing the groups by their year of release. It can therefore be concluded that the population committed to custodial facilities under § 21 para. 2 ACC has not changed fundamentally over the years. The first hypothesis thus has to be rejected. The observable decline in the recidivism rate of former detainees must therefore be traced back to other factors.

In contrast to the question of changes within the population, the data revealed various differences between the groups defined by the year of their release concerning the time offenders spent in confinement as well as the management of their release.

Generally, a process of professionalizing the system of the custodial measures can be observed. For example, structural changes were applied, installing institutions such as the ‘Appraisal Body for Perpetrators of Violence and Sex Offenders’. The mental health and correctional facilities consult this appraisal body, affiliated to the Federal Ministry of Constitutional Affairs, Reform, Deregulation and Justice, in questions such as granting certain privileges to detainees (e.g. spending time outside of the facility) or the circumstances of their release. The appraisal body supports the facility by providing a professional perspective either by studying the detainee’s file or by examining him directly. In addition, the ‘Clearing Centre for Custodial Sanctions’ was established also within the Federal Ministry for Constitutional Affairs, Reform, Deregulation and Justice. This focal point is staffed with experts on custodial facilities and is responsible for strategic and organisational questions.

Within the correctional facilities, more specialised prison guards as well as more psychologists and social workers take care of the detainees. In the interviews the experts reported that the cooperation between the various institutions involved (courts, correctional facilities, aftercare facilities, probation officers, etc.) has improved considerably over the years.

During their time in the confinement, the detainees received different kinds of treatment, depending on factors like availability, diagnoses, or their willingness to participate. For the purpose of the study, five categories of treatment were defined: individual care (e.g. psychotherapy), treatment within a group setting, psychiatric care, care provided by social workers, and occupational therapy. Comparing the groups defined by the year of release, no significant difference concerning these five types of treatment were identified.

When extracting the group of sex offenders difference concerning the treatment became apparent when comparing them by year of their release. In later years, these offenders received treatment in a group setting significantly more often; the same was true for care provided by the social workers. Furthermore, concurrent treatment by social workers and psychiatrists was also significantly more often applied in the group of offenders released in 2010 and 2011. Similar changes concerning the treatment could not be observed for the perpetrators of any other group of offences. This leads to the conclusion that in later years the treatment was matched more strongly to the offence committed, leading to substantial changes especially in the treatment of sex offenders. Additionally, further changes concerning sex offenders became apparent. The percentage of these detainees released into aftercare institutions increased from 53 % to 73 % significantly (p = .040) over the years. Further, the courts issued significantly more directives upon release. Since these changes concerning the group sex offenders became clear, the recidivism rate for this group was calculated, showing an almost significant connection (p = .051). 46 % of the sex offenders released in 2000 and 2001 reoffended within five years, whereas this was only true for 18 % of the sex offenders released in 2010 and 2011. This considerable decrease leads to the conclusion that the changes in treating these offenders helped reduce the recidivism rate of this important subgroup.

Comparing reoffenders with former detainees who did not reoffend regarding treatment received, certain differences emerged. It is noteworthy that concerning every observed difference the group of reoffenders were the ones who received less treatment compared to non-reoffenders. That was true for care provided by social workers (p = .015) as well as the combination of certain forms of treatments, e.g. therapy in a group setting and care provided by social workers (p = .032).

When an offender has undergone extensive treatment and a positive development becomes noticeable, a next step on the way to the conditional release can be so-called interruptions of custody, regulated in § 166 Corrections Act. For a certain period of time, the offender lives outside the custodial facility, testing his ability to comply with the demands of freedom. Often, the interruption of custody is conducted in an aftercare facility, where the offender can undergo further treatment. Thereby a certain level of control is still applied, while at the same time the abilities of the offender can be tested in an environment different from the one in prison. The percentage of offenders undergoing an interruption of custody before their release increased from 33 % to 64 % significantly (p = .007) from the group released in 2000/2001 to the detainees released in 2010/2011. At the same time, a differentiation of organisations offering aftercare has taken place, allowing for a more individual selection of the facility for each offender. Because of this noticeable development, the interview partners were asked for their opinion of the interruptions of custody. They unanimously responded that they thought them an important and valuable instrument in order to examine an offender’s development under realistic circumstances outside of confinement, while at the same time still being under the control of professionals. Additionally, interruptions of custody have another positive effect. During the time in the aftercare facility, the interruption can be terminated at any time should the offender refuse to comply with the demands as well as if a crisis stemming from his mental illness arises and the stay in the aftercare facility becomes too dangerous. In case of a termination, the offender is brought back into the custodial facility, where he can be stabilized, and reoffending can be prevented. If the instrument of interruption of custody did not exist, a release would have to take place without this try out. In these cases, a crisis could not be avoided if it occurred, because there is no option of bringing the offender back into confinement quickly. By implementing the possibility for interruptions of custody, the safety of the whole process was improved.

When the treatment within the custodial sanction as well as possible interruptions of custody have been successful, the offender can be released conditionally from confinement. Concerning the management of this conditional release, the data showed various changes over the years, while no differences became apparent when comparing reoffenders with non-reoffenders. As was expected, a majority of offenders stayed in confinement longer than their sentence had ordered them to. This could be observed for all years of release. However, the duration of the time spent in the custodial facility expanded significantly (p = .039): offenders released in 2000 and 2001 were detained for 56 months on average; this figure rose to 73 months on average for the group released in 2010 and 2011. In both groups, the majority of offenders went to live in an aftercare facility subsequent to their release. As was observed concerning the interruption of custody, the range of available institutions providing aftercare increased significantly over the years (p = .018). Contrary to what might be expected, the percentage of offenders who were able to secure a job upon release dropped from the first to the second group (p = .016).

Furthermore, the data showed considerable changes regarding the court directives issued upon release. The number of directives increased significantly over the years (p = .029), from one directive in most cases upon release in 2000 and 2001 to three or four directives for the offenders released in 2010 and 2011. Those directives were examined further, and it became apparent that the frequency of some specific directives had changed more than that of others. For example, offenders released in 2010/2011 received a directive concerning their place of residence significantly more often than those released 10 years prior (p = .009). While 50 % were ordered a specific place to live upon release in the first group, this percentage rose to 78 % in the second group. The same was true for the directive to avoid drinking alcohol and proving this to the court by undergoing regular alcohol tests (p = .000). This directive was issued to 11 % in 2000/2001, while in 2010/2011 53 % had to commit themselves to this demand. Contrary, a decline in the directive of attending psychotherapy from 52 % to 24 % also became apparent (p = .009). Ensuing, multivariate analyses were conducted to explore possible changes in the combination of directives. Concurrent directives regarding the abstinence from alcohol and the place of residence increased in frequency (from 7 % to 48 %, p = .000), as did the combination of abstinence from alcohol and compulsory attendance of treatment in a forensic-therapeutic centre (from 4 % to 23 %, p = .023). Furthermore, all of these three directives were issued together significantly more often in later years (from 0 % to 20 %, p = .010). When asked about circumstances necessary to facilitate a safe and successful release, the experts listed exactly these factors: a place of residence which can provide the offender with a combination of care and control, ongoing treatment, abstinence from alcohol and illicit drugs, and, if possible, the opportunity for work or an occupation providing structure during the day.

In addition to the opinion that taking place of residence in an aftercare is an important factor in avoiding reoffending, a legislative change in 2009 might also be responsible for the increase of releases into an aftercare facility.[51] § 179a Corrections Act now stipulates that the costs of living in such a facility have to be borne by the state, if a court directive is the reason for the offender to live there.[52] In order to facilitate this, the state can enter into contracts with the facilities in question.[53] If such a directive is issued upon release, its compliance has to be monitored by a judge. In one interview the judge complained that monitoring the directives is a time-consuming task and that not enough resources are employed to fulfil this duty. Additionally, there is no security in some cases regarding which costs are borne by the public authorities, complicating the work of the judges. Thus, it was proposed to install a centralized monitoring body within the Federal Ministry of Constitutional Affairs, Reform, Deregulation and Justice, responsible for handling all questions concerning the costs associated with the directives. Thereby, it would be easier for judges to concentrate on their responsibility of controlling the necessity of and the offender’s compliance with the directives.[54]

Once an offender is released from the custodial facility, two institutions become particularly important in supporting him: the aftercare facilities and the probationary services. The representatives of both institutions described certain changes in their work, which had taken place over the last years and which might also have contributed to the decrease of the reoffending rate.

The representatives of the aftercare facility described an extension of treatment possibilities as well as options for the residents to organise their free time. What is more, the caregivers would focus more strongly on exercising a certain level of control over the residents, thereby bridging the time of extensive control within the custodial sanction to the freedom experienced later by the offender when living in his own home. Additionally, regular alcohol tests as well as tests for the use of illicit drugs are carried out, since these substances play a vital role when it comes to the danger of reoffending. When asked about their experiences in cooperating with the aftercare institutions, the interview partners responded positively for the most part. The judges as well as the psychiatrists and the representatives of the correctional facilities viewed the accommodation of the offenders in an aftercare facility almost as a condition for the release.

The representative of the probationary services also described changes concerning his institution’s understanding of its role upon release of the perpetrator. While in earlier years they had almost solely focussed on supporting the client, they now concentrate more strongly on a certain level of control, seeing this as part of the supporting process. Additionally, more resources are invested into the diagnostic process at the beginning of the supervision, identifying the specific needs and challenges for each client. Finally, the process of documentation had been improved, in order to guarantee a professional handling even in complicated cases. Various interview partners emphasized the quality of the work the probation officers are providing as well as the constructive cooperation they have with this institution.

Additionally to giving an insight into their work, the experts also raised demands and made proposals on how to improve the situation for the system of custodial sanctions. One proposal stuck out insofar as six out of seven interlocutors brought it up without a specific question of the interviewer: they demanded installing the possibility for crisis intervention. Currently, if a released offender enters a state of crisis, when his health status deteriorates or when the risk of reoffending becomes clear, the sole possible reaction is to recommit him into the custodial facility. However, this is a lengthy and slow process and leads to the offender being committed completely back into custody. According to the experts, this full recommittal is not necessary in all cases. Therefore, they propose the possibility to confine the offender temporarily in a closed facility, in order to stabilize him during the crisis. Once his condition has improved, he can be released again. This confinement should be possible for a maximum of three months with the possibility of one extension for the same period. By introducing such a system, experts expect release rates to increase, because it offers judges a certain amount of leeway.

In conclusion, the data showed that substantial changes were implemented concerning the time the offenders spent in the custodial facility as well as the circumstances of conditional releases. It can be assumed that these changes have contributed to the decline of the recidivism rate, hereby confirming the second hypothesis.

The final hypothesis tested was that the selection process between detainees truly ready for release and offenders needing more time in the custodial facility before their conditional release improved over the years, leading to a higher percentage of offenders with a lower risk for reoffending upon release. Several factors seem to support this assumption, thus confirming the third hypothesis.

Firstly, changes concerning the interruption of custody have already been explained above. The frequency of applying this instrument prior to conditional release was significantly higher in later years. All experts emphasised the importance of this period of time giving the offender the possibility to experience a much higher level of freedom than in the custodial facility while simultaneously receiving both support and control from a professional organisation. In case the offender proves to not be ready for this amount of freedom, he can easily and quickly be recommitted into the custodial facility, possibly avoiding otherwise occurring offences. The interruption of custody thereby seems to have a direct impact on the recidivism rate.

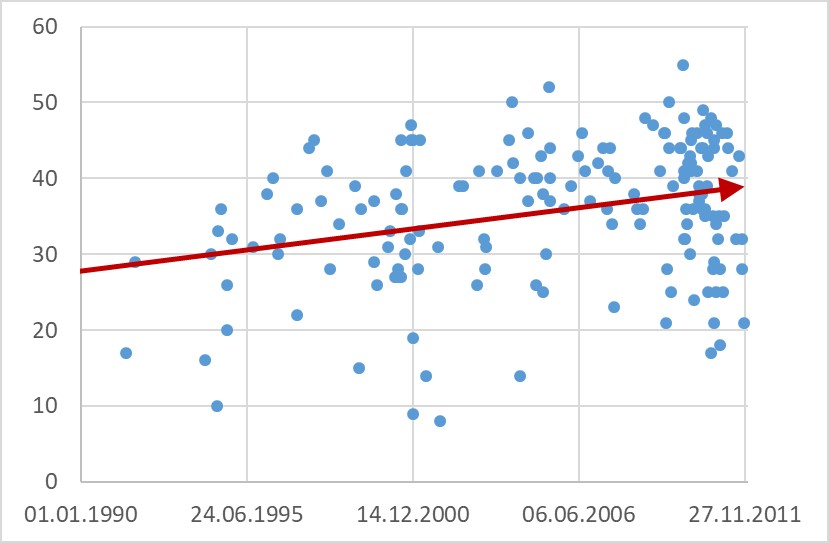

Beyond that, the expert reports are of great importance for the question of selection, since the judges rely strongly on the expert’s assessment when coming to a decision about committal or release. Thus, these expert reports were examined thoroughly as described above, evaluating every report on the basis of a list of criteria.[55] For every report a total value was calculated, adding the scores the report obtained for each criterion. While between reoffenders and non-reoffenders no difference emerged, considerable differences between the groups defined by the year of release were detected, showing that the quality of expert reports used in 2010 and 2011 was significantly higher than in the group of offenders released in 2000 and 2001. When examining the scores of each report arranged by the date of its creation (the study included reports from 1986 to 2011), a clear trend of an increase in quality over the years became apparent.

Graph 6: Distribution of the scores obtained by the examined expert reports, 1994 – 2011

Over the years, the average length of the expert reports has increased considerably, a first indicator for the rise in quality. Variables which are highly important for a solid assessment of the offender, such as the use of psychometric tests or discussing the individual risk factors, were covered significantly more often in the reports of the second group. In order to make a reliable prognosis, a report has to establish an individual hypothesis concerning the delinquency of the offender examined, explaining the origin of his conduct and suggesting measures of treatment.[56] This demand was met significantly more often in later years, as can be seen in the increased fulfilment of criteria such as ‘analysis of the offender’s delinquency, its background and causes’ or ‘specifying the circumstances under which the prognosis is valid and listing measures for organizing the circumstances for a successful legal probation in line with the individual risk management’. Reports produced upon release in the group of offenders released in 2010 and 2011 also contained significantly more detailed suggestions for court directives. As explained above, the handling of court directives has changed considerably over the years. The data concerning the expert reports as well as information given by the judges and the psychiatrist in the interview allow for the conclusion that this change can be traced back to the work of the experts in assessing the offender and proposing measures around the conditional release.

In summary, it became apparent that the quality of the expert reports had increased considerably over the years, allowing for the assumption that this contributed to the decline of the recidivism rate. This result is supported by a recent German study showing reports complying with the criteria under consideration also deliver more accurate results in terms of predicting recidivism.[57]

The changes described concerning the work of the experts are undoubtedly positive. However, there is still considerable room for improvement. Within the system applied for measuring the quality of a report using the list of criteria, a maximum of 68 points can be reached. On average, the reports produced upon release in the second group, which were significantly better than the ones in the first group, reached 37 points. The highest score attained by a report within this study was 55 points. Therefore, further efforts need to be made to continue the positive development concerning the expert reports and to further enhance the quality of their important work.

In order to achieve this goal various steps should be taken. Currently, experts are not obliged to comply with any quality standards when producing their reports for the court. While the data confirm that the fulfillment of the criteria under consideration has increased over the years, complying with them is still not mandatory for the experts. Therefore, binding quality standards should be established, thus giving the court the possibility to assess the value of the report. Additionally, experts should have to undergo specialized training before operating for the courts. Currently, training – for example the additional training for forensic prognosis offered by the Austrian Medical Chamber – is only voluntary. What is more, experts need to be paid appropriately for their work. While this seems to be the case in some parts of Austria, a nationwide unified system of compensation needs to be established. Finally, it would be preferable that an offender is not only examined by a single expert but by a multidisciplinary team of experts, combining various disciplines because in some cases, other professions might be crucial for thoroughly assessing the situation, such as social workers or pedagogic experts in addition to the expertise of psychiatrists and psychologists.

In conclusion, the data produced evidence that the decline of the recidivism rate concerning mentally ill but accountable offenders can be traced back to changes both in the treatment available within the custodial facilities and the management of conditional releases and to an increase in the quality of the expert reports used by the courts to base their decisions on. In contrast, almost no changes concerning the population of the detainees released in 2000/2001 and 2010/2011 were detected. While the first hypothesis therefore has to be rejected, the second and third hypotheses have been confirmed.

The results discussed here lead to several propositions on how to further improve the situation within custodial facilities and subsequently hopefully further lower the recidivism rate. In accordance with the demands of the interview partners, the implementation of a system for a temporary committal in the wake of a crisis is proposed. Thus, judges might be less restrictive when it comes to a decision concerning the conditional release, as this system would constitute a safety net in order to avoid reoffending. As described above, several changes concerning the production of the expert reports are necessary, starting with mandatory training and leading to binding quality standards and appropriate remuneration. On the other hand, successful practices, such as the interruption of custody, should be maintained or even expanded.

Many of the changes suggested here were already contained in the final report the expert working group delivered in 2015[58] as well as in the proposal for new legislation published in 2017[59], which never entered the parliamentary legislative process. When asked about his opinion on necessary changes for the system of custodial measures in Austria, the representative of the probationary services replied frustratedly that ‘concerning no other area of legislation, the complete concepts are kept in the drawer’. The author agrees with this statement. Many results obtained in the present study support the proposals made by the leading experts in recent years. It is now up to policy makers to implement these proposals into new legislation.

Donald Andrews and James Bonta, The psychology of Criminal Conduct, 5th edn. (New Providence, NJ: Matthew Bende & Company, 2010)

Arbeitsgruppe Maßnahmenvollzug, Bericht an den Bundesminister für Justiz über die erzielten Ergebnisse, BMJ-V70301/0061-III 1/2014, available at https://www.justiz.gv.at/file/2c94848a4b074c31014b3ad6caea0a71.de.0/bericht%20ag%20maßnahmenvollzug.pdf

Alois Birklbauer, ‘Der Umgang mit psychisch kranken Rechtsbrechern: Auf dem Weg zur lebenslangen Sicherungsverwahrung?’ (2013) Journal für Strafrecht 141-151

Axel Boetticher, Hans-Ludwig Kröber, Rüdiger Müller-Isberner, Klaus Böhm, Reinhard Müller-Metz and Thomas Wolf, ‘Mindestanforderungen für Prognosegutachten’ (2006) Neue Zeitschrift für Strafrecht 537-544

Karin Bruckmüller, Die strafrechtliche Behandlung der Rückfälligkeit im österreichischen StGB unter Einbeziehung kriminologischer Aspekte (Wien: Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 2011)

Christine Brugger, ‘Psychologische und psychiatrische Sachverständigengutachten zur bedingten Entlassung Untergebrachter nach § 21 Abs 2 öStGB’, in Karin Gutiérrez-Lobos (ed.), 25 Jahre Maßnahmenvollzug – eine Zwischenbilanz (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlag, 2002) 31-41

Bundesministerium für Justiz, Erlass vom 21. September 2007 über die neue Fachgruppen- und Fachgebietseinteilung für Gerichtssachverständige sowie die Sprachen der GerichtsdolmetscherInnen in der SDG-Liste (Nomenklatur–Erlass 2007 Teil II), JMZ 11852B/15/I 6/07, available at https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/Erlaesse/ERL_BMJ_20070921_11852B_15_I6_07/ERL_BMJ_20070921_11852B_15_I6_07.pdf

Bundesministerium für Justiz, Strafvollzug in Österreich (Wien, 2016), available at https://www.justiz.gv.at/file/2c9484853e44f8f9013ef9d9e2b928dd.de.0/strafvollzug_broschuere_2016_download.pdf

Bundesministerium für Justiz, Sicherheitsbericht 2016 – Bericht über die Tätigkeit der Strafjustiz (Wien, 2017), available at https://www.bmi.gv.at/508/files/SIB_2016/04_SIB2016-BMJ-Teil_web.pdf

Bundesministerium für Verfassung, Reformen, Deregulierung und Justiz, Sicherheitsbericht 2017 – Bericht über die Tätigkeit der Strafjustiz (Wien, 2018), available at https://www.bmi.gv.at/508/files/SIB_2017/04_SIB_2017-Justizteil_web.pdf

Jeremy Coid, Nicole Hickey, Nadji Kathan, Tianquiang Zhang and Min Yang, ‘Patients discharged from medium secure forensic psychiatry services: reconvictions and risk factors’ (2007) British Journal of Psychiatry 223-229

Karl Drexler and Thomas Weger, ‘§ 164 StVG’, in Karl Drexler and Thomas Weger (eds.), StVG – Strafvollzugsgesetz, 4th edn. (Wien: Manz, 2018)

Karl Drexler and Thomas Weger, ‘§ 179a StVG’, in Karl Drexler and Thomas Weger (eds.), StVG – Strafvollzugsgesetz, 4th edn. (Wien: Manz, 2018)

Peter Fiedler and Sabine C. Herpertz, Persönlichkeitsstörungen (Weinheim Basel: Beltz, 2016)

Fritjof von Franqué, ‘Strukturierte, professionelle Risikobeurteilungen’, in Martin Rettenberger and Fritjof von Franqué (eds.), Handbuch kriminalprognostischer Verfahren (Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2013) 357-380

Helmut Fuchs and Ingeborg Zerbes, Strafrecht – Allgemeiner Teil I, 10th edn. (Wien: Verlag Österreich, 2018)

Stefan Fuchs, ‘Der österreichische Maßnahmenvollzug an „geistig abnormen Rechtsbrechern” – Ausgewählte Aspekte des Reformbedarfs’ (2015) Forensische Psychiatrie & Psychotherapie 195-207

Stefan Fuchs, Monitoring des Maßnahmenvollzuges an geistig abnormen Rechtsbrechern gemäß § 21 Abs.2 StGB – Bericht für das Jahr 2014 (Wien, 2015)

Stefan Fuchs, Monitoring des Maßnahmenvollzuges an geistig abnormen Rechtsbrechern gemäß § 21 Abs.1 StGB – Bericht für das Jahr 2017 (Wien, 2018)

Stefan Fuchs, Monitoring des Maßnahmenvollzuges an geistig abnormen Rechtsbrechern gemäß § 21 Abs.2 StGB – Bericht für das Jahr 2017 (Wien, 2018)

Stefan Fuchs, Monitoring des Maßnahmenvollzuges an geistig abnormen Rechtsbrechern gemäß § 21 Abs.1 StGB – Bericht für das Jahr 2018 (Wien, 2019)

Stefan Fuchs, Monitoring des Maßnahmenvollzuges an geistig abnormen Rechtsbrechern gemäß § 21 Abs.2 StGB – Bericht für das Jahr 2018 (Wien, 2019)

Christian Grafl, Wolfgang Gratz, Frank Höpfel, Christine Hovorka, Arno Pilgram, Hans-Valentin Schroll and Richard Soyer, ‘Kriminalpolitische Initiative: Mehr Sicherheit durch weniger Haft!’ (2009) Journal für Rechtspolitik 152-156

Gregor Groß, Deliktbezogene Rezidivraten von Straftätern im internationalen Vergleich (München, 2004)

Karin Gutiérrez-Lobos, ‘Psychiatrische Gutachten im Spannungsfeld zwischen Medizin, Recht und Gesellschaft’ (2004) juridikum 203-206

Gernot Hahn and Michael Wörthmüller, Forensische Nachsorgeambulanzen in Deutschland. Patientenstruktur, Interventionsformen und Verlauf in der Nachsorge psychisch kranker Straftäter nach Entlassung aus dem Maßregelvollzug gem. § 63 StGB (Coburg: ZKS-Verlag, 2011)

Robert Jerabek, ‘§ 48 StGB’, in Frank Höpfel and Eckart Ratz (eds.), Wiener Kommentar zum Strafgesetzbuch (Wien: Manz, 2014)

Harald Krammer, ‘Die gesonderte Honorierung von psychiatrischen Kriminalprognostikgutachten nach § 34 GebAG – und nicht nach § 43 Abs 1 Z 1 GebAG – eine Judikaturwende’ (2017) Sachverständige 100-108

Franziska Kunzl and Friedemann Pfäfflin, ‘Qualitätsanalyse österreichischer Gutachten zur Zurechnungsfähigkeit und Gefährlichkeitsprognose’ (2011) Recht & Psychiatrie 152-159

Franziska Kunzl, Qualitätsanalyse österreichischer Gutachten zur Zurechnungsfähigkeit und Gefährlichkeitsprognose (Ulm, 2011)

Helmut Kury, ‘Zur Qualität forensisch-psychiatrischer und -psychologischer kriminalprognostischer Gutachten – Ergebnisse einer empirischen Untersuchung’, in Helmut Pollähne and Christa Lange-Joest (eds.), Achtung: Begutachtung! Sachverständige in Justiz und Gesellschaft: Erwartungen und Verantwortung (Berlin: Institut für Konfliktforschung, 2017) 115-153

Christian Manquet, ‘Überlegungen zu einer zeitgemäßen Neugestaltung der ‚geistigen oder seelischen Abartigkeit höheren Grades’ als Zulässigkeitsvoraussetzung für eine mit Freiheitsentziehung verbundene vorbeugende Maßnahme’, in Bundesministerium für Justiz (ed.), StGB 2015 und Maßnahmenvollzug: RichterInnenwoche 2014 in Saalfelden am Steinernen Meer 19.-23. Mai 2014 (Wien: Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 2015) 139-158

Rainer J. Nimmervoll, ‘§ 24 StGB’, in Otto Triffterer, Christian Rosbaud and Hubert Hinterhofer (eds.), Salzburger Kommentar zum Strafgesetzbuch (Salzburg: LexisNexis, 2019)

Rainer J. Nimmervoll, ‘§ 25 StGB’, in Otto Triffterer, Christian Rosbaud and Hubert Hinterhofer (eds.), Salzburger Kommentar zum Strafgesetzbuch (Salzburg: LexisNexis, 2019)

Manfred Novak and Stephanie Krisper, ‘Der österreichische Maßnahmenvollzug und das Recht auf persönliche Freiheit’ (2013) Europäische Grundrechte-Zeitschrift 645-661

Sabine Nowara, Gefährlichkeitsprognosen bei psychisch kranken Straftätern (München: Wilhelm Fink, 1995)

Österreichischer Rechnungshof, Maßnahmenvollzug für geistig abnorme Rechtsbrecher (Wien, 2010/11), available at https://www.rechnungshof.gv.at/rh/home/home/Massnahmenvollzug_fuer_geistig_abnorme_Rechtsbrecher

Friedemann Pfäfflin, Vorurteilsstruktur und Ideologie psychiatrischer Gutachten über Sexualstraftäter – Beiträge zur Sexualforschung 57 (Stuttgard: Enke, 1978)

Eberhard Pieber, ‘§ 179a StVG’, in Frank Höpfel and Eckart Ratz (eds.), Wiener Kommentar zum Strafgesetzbuch (Wien: Manz, 2014)

Eckart Ratz, ‘§ 25 StGB’, in Frank Höpfel and Eckart Ratz (eds.), Wiener Kommentar zum Strafgesetzbuch (Wien: Manz, 2014)

Wolfgang Stangl, Alexander Neumann and Norbert Leonhardmair, Welcher organisatorischen Schritte bedarf es, um die Zahl der Einweisungen in den Maßnahmenvollzug zu verringern? (Wien, 2012)

Wolfgang Stangl, Alexander Neumann and Norbert Leonhardmair, ‘Von Krank-Bösen und Bös-Kranken. Der österreichische Maßnahmenvollzug’ (2015) Journal für Strafrecht 95-111

Barbara Tröbinger and Martin Kitzberger, ‘Standardisierte Risikobeurteilung’, in Bundesministerium für Justiz (ed.), StGB 2015 und Maßnahmenvollzug: RichterInnenwoche 2014 in Saalfelden am Steinernen Meer 19.-23. Mai 2014 (Wien: Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 2015) 185-204

Maximilian Wertz and Helmut Kury, ‘Verbesserung der Qualität von Prognosegutachten seit der Veröffentlichung von Mindeststandards? Eine empirische Validierung im Zeitverlauf’, in Jürgen Müller, Peer Briken, Michael Rösler, Marcus Müller, Daniel Turner and Wolfgang Retz (eds.), EFPPP Jahrbuch 2017 – Empirische Forschung in der Forensischen Psychiatrie, Psychologie und Psychotherapie (Berlin: MWV: Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 2017) 107-124

World Health Organization, International Classification of Diseased (ICD), available at https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en#/V

[*]MMag.a Dr.in Monika Stempkowski is a post-doctoral research assistant at the department of criminal law and criminology, University of Vienna, monika.stempkowski@univie.ac.at.

[1]Austrian Criminal Code (ACC), Austrian Federal Law Gazette No. 60/1974, 29.01.1974, last amended by Austrian Federal Law Gazette I No. 105/2019, 29.10.2019.

[2]Wolfgang Stangl, Alexander Neumann and Norbert Leonhardmair, ‘Von Krank-Bösen und Bös-Kranken. Der österreichische Maßnahmenvollzug’ (2015) Journal für Strafrecht 95-111; Stefan Fuchs, ‘Der österreichische Maßnahmenvollzug an „geistig abnormen Rechtsbrechern” – Ausgewählte Aspekte des Reformbedarfs’ (2015) Forensische Psychiatrie & Psychotherapie 195-207.

[3]Franziska Kunzl and Friedemann Pfäfflin, ‘Qualitätsanalyse österreichischer Gutachten zur Zurechnungsfähigkeit und Gefährlichkeitsprognose’ (2011) Recht & Psychiatrie 152-159.

[4]Stefan Fuchs, Monitoring des Maßnahmenvollzuges an geistig abnormen Rechtsbrechern gemäß § 21 Abs.2 StGB – Bericht für das Jahr 2018 (Wien, 2019), p. 19.

[5]Helmut Fuchs and Ingeborg Zerbes, Strafrecht – Allgemeiner Teil I, 10th edn. (Wien: Verlag Österreich, 2018), pp. 21 et seqq.

[6]Fuchs and Zerbes, ‘Strafrecht’, pp. 228 et seqq.

[7]Karl Drexler and Thomas Weger, ‘§ 164 StVG’, in Karl Drexler and Thomas Weger (eds.), StVG – Strafvollzugsgesetz, 4th edn. (Wien: Manz, 2018), para. 1; Alois Birklbauer, ‘Der Umgang mit psychisch kranken Rechtsbrechern: Auf dem Weg zur lebenslangen Sicherungsverwahrung?’ (2013) Journal für Strafrecht 141-151.

[8]Rainer J. Nimmervoll, ‘§ 25 StGB’, in Otto Triffterer, Christian Rosbaud and Hubert Hinterhofer (eds.), Salzburger Kommentar zum Strafgesetzbuch (Salzburg: LexisNexis, 2019), para. 2; Eckart Ratz, ‘§ 25 StGB’, in Frank Höpfel and Eckart Ratz (eds.), Wiener Kommentar zum Strafgesetzbuch (Wien: Manz, 2014), para. 1.

[9]Nimmervoll, ‘§ 25 StGB’, para. 5; Ratz, ‘§ 25 StGB’, para. 3.

[10]Rainer J. Nimmervoll, ‘§ 24 StGB’, in Otto Triffterer, Christian Rosbaud and Hubert Hinterhofer (eds.), Salzburger Kommentar zum Strafgesetzbuch (Salzburg: LexisNexis, 2019), para. 3.

[11]Robert Jerabek, ‘§ 48 StGB’, in Frank Höpfel and Eckart Ratz (eds.), Wiener Kommentar zum Strafgesetzbuch (Wien: Manz, 2014), para. 4.

[12]Bundesministerium für Justiz, Strafvollzug in Österreich (Wien, 2016), available at https://www.justiz.gv.at/file/2c9484853e44f8f9013ef9d9e2b928dd.de.0/strafvollzug_broschuere_2016_download.pdf, p. 71.

[13]Corrections Act, Austrian Federal Law Gazette No. 144/1969, 20.5.1969, last amended by Austrian Federal Law Gazette I No. 100/2018, 22.12.2018.

[14]S. Fuchs, ‘Monitoring § 21 Abs 2 StGB 2018’, p. 11.

[15]Österreichischer Rechnungshof, Maßnahmenvollzug für geistig abnorme Rechtsbrecher, available at https://www.rechnungshof.gv.at/rh/home/home/Massnahmenvollzug_fuer_geistig_abnorme_Rechtsbrecher, p. 105-6.

[16]Manfred Novak and Stephanie Krisper, ‘Der österreichische Maßnahmenvollzug und das Recht auf persönliche Freiheit’ (2013) Europäische Grundrechte-Zeitschrift 645-661; Christian Manquet, ‘Überlegungen zu einer zeitgemäßen Neugestaltung der ‚geistigen oder seelischen Abartigkeit höheren Grades‘ als Zulässigkeitsvoraussetzung für eine mit Freiheitsentziehung verbundene vorbeugende Maßnahme’, in Bundesministerium für Justiz (ed.), StGB 2015 und Maßnahmenvollzug: RichterInnenwoche 2014 in Saalfelden am Steinernen Meer 19.-23. Mai 2014 (Wien: Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 2015) 139-158; Christian Grafl, Wolfgang Gratz, Frank Höpfel, Christine Hovorka, Arno Pilgram, Hans-Valentin Schroll and Richard Soyer, ‘Kriminalpolitische Initiative: Mehr Sicherheit durch weniger Haft!’ (2009) Journal für Rechtspolitik 152-156, p. 156.

[17]See https://www.falter.at/archiv/wp/die-schande-von-stein.

[18]Arbeitsgruppe Maßnahmenvollzug, Bericht an den Bundesminister für Justiz über die erzielten Ergebnisse, BMJ-V70301/0061-III 1/2014, available at https://www.justiz.gv.at/file/2c94848a4b074c31014b3ad6caea0a71.de.0/bericht%20ag%20maßnahmenvollzug.pdf, pp. 56 et seqq.

[19]Maßnahmen-Reform-Gesetz 2017, draft legislation, published online: https://www.justiz.gv.at/web2013/file/2c94848a5d559217015d55bc9d1d4483.de.0/maßnahmen-reform-gesetz%202017-text.pdf?forcedownload=true.

[20]Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP), Austrian Federal Law Gazette No. 631/1975, 30.12.1975, last amended by Austrian Federal Law Gazette I No. 105/2019, 29.10.2019.

[21]Bundesministerium für Justiz, Sicherheitsbericht 2016 – Bericht über die Tätigkeit der Strafjustiz (Wien, 2017), available at https://www.bmi.gv.at/508/files/SIB_2016/04_SIB2016-BMJ-Teil_web.pdf, p. 115; Stefan Fuchs, Monitoring des Maßnahmenvollzuges an geistig abnormen Rechtsbrechern gemäß § 21 Abs.1 StGB – Bericht für das Jahr 2017 (Wien, 2018), p. 8; Stefan Fuchs, Monitoring des Maßnahmenvollzuges an geistig abnormen Rechtsbrechern gemäß § 21 Abs.2 StGB – Bericht für das Jahr 2017 (Wien, 2018), p. 5; Stefan Fuchs, Monitoring des Maßnahmenvollzuges an geistig abnormen Rechtsbrechern gemäß § 21 Abs.1 StGB – Bericht für das Jahr 2018 (Wien, 2019), p. 14.

[22]Bundesministerium für Verfassung, Reformen, Deregulierung und Justiz, Sicherheitsbericht 2017 – Bericht über die Tätigkeit der Strafjustiz (Wien, 2018), available at https://www.bmi.gv.at/508/files/SIB_2017/04_SIB_2017-Justizteil_web.pdf, pp. 103 & 112.

[23]Bundesministerium für Verfassung, Reformen, Deregulierung und Justiz, ‘Sicherheitsbericht 2017’, available at https://www.bmi.gv.at/508/files/SIB_2017/04_SIB_2017-Justizteil_web.pdf, pp. 113 et seqq.; S. Fuchs, ‘Monitoring § 21 Abs 2 StGB 2018’, p. 5.

[24]S. Fuchs, ‘Monitoring § 21 Abs 2 StGB 2018’, pp. 7-8; Bundesministerium für Justiz, ‘Sicherheitsbericht 2016’, available at https://www.bmi.gv.at/508/files/SIB_2016/04_SIB2016-BMJ-Teil_web.pdf, pp. 114 et seqq.

[25]Stangl, Neumann and Leonhardmair, ‘Von Krank-Bösen und Bös-Kranken’, p. 101.

[26]S. Fuchs, ‘Monitoring § 21 Abs 2 StGB 2018’, p. 13.

[27]S. Fuchs, ‘Monitoring § 21 Abs 2 StGB 2018’, pp. 15 et seqq.

[28]Wolfgang Stangl, Alexander Neumann and Norbert Leonhardmair, Welcher organisatorischen Schritte bedarf es, um die Zahl der Einweisungen in den Maßnahmenvollzug zu verringern? (Wien, 2012), pp. 26 et seqq.

[29]World Health Organization, International Classification of Diseased (ICD), available at https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en#/F60-F69.

[30]Peter Fiedler and Sabine C. Herpertz, Persönlichkeitsstörungen (Weinheim Basel: Beltz, 2016), pp. 21 et seqq.

[31]Stangl, Neumann and Leonhardmair, ‘organisatorische Schritte’, pp. 25 et seqq.

[32]Stefan Fuchs, Monitoring des Maßnahmenvollzuges an geistig abnormen Rechtsbrechern gemäß § 21 Abs.2 StGB – Bericht für das Jahr 2014 (Wien, 2015), pp. 16 et seqq.

[33]Fines as well as diversional measures are not included into this statistic.

[34]Bundesministerium für Verfassung, Reformen, Deregulierung und Justiz, ‘Sicherheitsbericht 2017’, available at https://www.bmi.gv.at/508/files/SIB_2017/04_SIB_2017-Justizteil_web.pdf, pp. 181 et seqq.

[35]S. Fuchs, ‘Monitoring § 21 Abs 2 StGB 2018’, p. 20.

[36]Karin Gutiérrez-Lobos, ‘Psychiatrische Gutachten im Spannungsfeld zwischen Medizin, Recht und Gesellschaft’ (2004) juridikum 203-206.

[37]Friedemann Pfäfflin, Vorurteilsstruktur und Ideologie psychiatrischer Gutachten über Sexualstraftäter – Beiträge zur Sexualforschung 57 (Stuttgard: Enke, 1978); Sabine Nowara, Gefährlichkeitsprognosen bei psychisch kranken Straftätern (München: Wilhelm Fink, 1995).

[38]Kunzl and Pfäfflin, ‘Qualitätsanalyse’, p. 152; Franziska Kunzl, Qualitätsanalyse österreichischer Gutachten zur Zurechnungsfähigkeit und Gefährlichkeitsprognose (Ulm, 2011), p. 28

[39]Fees Claims Act, Austrian Federal Law Gazette No. 136/1975, 14.3.1975, last amended by Austrian Federal Law Gazette I No. 44/2019, 28.5.2019.

[40]Grafl, Gratz, Höpfel, Hovorka, Pilgram, Schroll and Soyer, ‘Kriminalpolitische Initiative’, p. 154.

[41]Bundeministerium für Justiz, Erlass vom 21. September 2007 über die neue Fachgruppen- und Fachgebietseinteilung für Gerichtssachverständige sowie die Sprachen der GerichtsdolmetscherInnen in der SDG-Liste (Nomenklatur-Erlass 2007 Teil II), JMZ 11852B/15/I 6/07, available at https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/Erlaesse/ERL_BMJ_20070921_11852B_15_I6_07/ERL_BMJ_20070921_11852B_15_I6_07.pdf.

[42]Higher Regional Court Vienna OLG Wien 7.3.2017, 17 Bs 58/17d; Higher Regional Court Vienna OLG Wien 28.3.2017, 21 Bs 49/17k; selected decisions of the Higher Regional Courts can be accessed via https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Jus/ with their case number. See also Harald Krammer, ‘Die gesonderte Honorierung von psychiatrischen Kriminalprognostikgutachten nach § 34 GebAG – und nicht nach § 43 Abs 1 Z 1 GebAG – eine Judikaturwende’ (2017) Sachverständige 100-108.

[43]Arbeitsgruppe Maßnahmenvollzug, ‘Bericht’, p. 67.

[44]Grafl, Gratz, Höpfel, Hovorka, Pilgram, Schroll and Soyer, ‘Kriminalpolitische Initiative’, p. 154.

[45]Christine Brugger, ‘Psychologische und psychiatrische Sachverständigengutachten zur bedingten Entlassung Untergebrachter nach § 21 Abs 2 öStGB’, in Karin Gutiérrez-Lobos (ed.), 25 Jahre Maßnahmenvollzug – eine Zwischenbilanz (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlag, 2002) 31-41, p. 37.

[46]Axel Boetticher, Hans-Ludwig Kröber, Rüdiger Müller-Isberner, Klaus Böhm, Reinhard Müller-Metz and Thomas Wolf, ‘Mindestanforderungen für Prognosegutachten’ (2006) Neue Zeitschrift für Strafrecht 537-544.

[47]S. Fuchs, ‘Monitoring § 21 Abs 2 StGB 2018’, pp. 19 et seqq.

[48]Cf. S. Fuchs, ‘Der österreichische Maßnahmenvollzug’, p. 195.

[49]E.g. Donald Andrews and James Bonta, The psychology of Criminal Conduct, 5th edn. (New Providence, NJ: Matthew Bende & Company, 2010), pp. 193 et seqq.; Barbara Tröbinger and Martin Kitzberger, ‘Standardisierte Risikobeurteilung’, in Bundesministerium für Justiz (ed.), StGB 2015 und Maßnahmenvollzug: RichterInnenwoche 2014 in Saalfelden am Steinernen Meer 19.-23. Mai 2014 (Wien: Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 2015) 185-204, p. 195; Jeremy Coid, Nicole Hickey, Nadji Kathan, Tianquiang Zhang and Min Yang, ‘Patients discharged from medium secure forensic psychiatry services: reconvictions and risk factors’ (2007) British Journal of Psychiatry 223-229; Gregor Groß, Deliktbezogene Rezidivraten von Straftätern im internationalen Vergleich (München, 2004), pp. 39 et seqq; Gernot Hahn and Michael Wörthmüller, Forensische Nachsorgeambulanzen in Deutschland. Patientenstruktur, Interventionsformen und Verlauf in der Nachsorge psychisch kranker Straftäter nach Entlassung aus dem Maßregelvollzug gem. § 63 StGB (Coburg: ZKS-Verlag, 2011); Karin Bruckmüller, Die strafrechtliche Behandlung der Rückfälligkeit im österreichischen StGB unter Einbeziehung kriminologischer Aspekte (Wien: Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 2011), pp. 225 et seqq.

[50]Due to the very small sample number, female offenders were not included into the study.

[51]Second Protection from Violence Act, Austrian Federal Law Gazette I No. 40/2009, 8.4.2009.

[52]Karl Drexler and Thomas Weger, ‘§ 179a StVG’, in Karl Drexler and Thomas Weger (eds.), StVG – Strafvollzugsgesetz, 4th edn. (Wien: Manz, 2018), paras. 2 et seqq.

[53]Eberhard Pieber, ‘§ 179a StVG’, in Frank Höpfel and Eckart Ratz (eds.), Wiener Kommentar zum Strafgesetzbuch (Wien: Manz, 2014), para. 6.

[54]This proposal was discussed during an expert group meeting at the ‘Stodertal Forensiktage 2018’.

[55]Boetticher, Kröber, Müller-Isberner, Böhm, Müller-Metz and Wolf, ‘Mindestanforderungen’, p. 537.

[56]Fritjof von Franqué, ‘Strukturierte, professionelle Risikobeurteilungen’, in Martin Rettenberger and Fritjof von Franqué (eds.), Handbuch kriminalprognostischer Verfahren (Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2013) 357-380.

[57]Helmut Kury, ‘Zur Qualität forensisch-psychiatrischer und -psychologischer kriminalprognostischer Gutachten – Ergebnisse einer empirischen Untersuchung’, in Helmut Pollähne and Christa Lange-Joest (eds.), Achtung: Begutachtung! Sachverständige in Justiz und Gesellschaft: Erwartungen und Verantwortung (Berlin: Institut für Konfliktforschung, 2017) 115-153, p. 137; Maximilian Wertz and Helmut Kury, ‘Verbesserung der Qualität von Prognosegutachten seit der Veröffentlichung von Mindeststandards? Eine empirische Validierung im Zeitverlauf’, in Jürgen Müller, Peer Briken, Michael Rösler, Marcus Müller, Daniel Turner and Wolfgang Retz (eds), EFPPP Jahrbuch 2017 – Empirische Forschung in der Forensischen Psychiatrie, Psychologie und Psychotherapie (Berlin: MWV: Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 2017) 107-124.

[58]Arbeitsgruppe Maßnahmenvollzug, ‘Bericht’, pp. 56 et seqq.

[59]Maßnahmen-Reform-Gesetz 2017, published online: https://www.justiz.gv.at/web2013/file/2c94848a5d559217015d55bc9d1d4483.de.0/maßnahmen-reform-gesetz%202017-text.pdf?forcedownload=true.

University of Vienna Law Review, Vol. 3 (2019), pp. 42-72, https://doi.org/10.25365/vlr-2019-3-1-42.